The Heart of No Place as a Reinterpretation of Works by Yoko Ono in the Digital Age

by Rika Ohara

An image created inside a computer resides in no place or time at all. –– Michael Rush, 1999

MESSAGE IS THE MEDIUM Y.O. ’69

|

The Heart of No Place (written in the late 1990s and produced 2000-2009) is an experimental narrative film, and as such, it aims to create an emotional experience rather than to engage the viewer in a discourse. At the same time, it was born on a formal and conceptual migratory arc from performance-, installation and other hybrid practices into the digital media, and contains thoughts on the relationship between the human conditions, media and technology. These ideas are incorporated into the narrative as lines spoken by characters varying in personality and in their relationship to Y., in a series of "faux-interviews" and images and titles woven throughout the film.

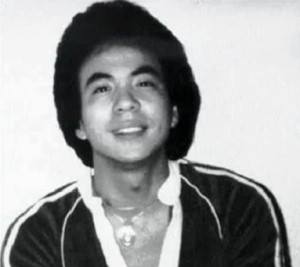

It was during the years of "Trade War with Japan," that I had

the idea of working with a story revolving around the life and work of Yoko

Ono. I was working on

media-and-dance performance piece Tokyo Rose, which juxtaposed the

late 20th-century’s "Trade War" in the mass media with WWII

propaganda attributed to a Los Angeles-born Japanese American, Iva Toguri.

American reactions to "Trade War" were rife with anti-Japanese (or

anti-Asian, as the murder of Vincent Chin

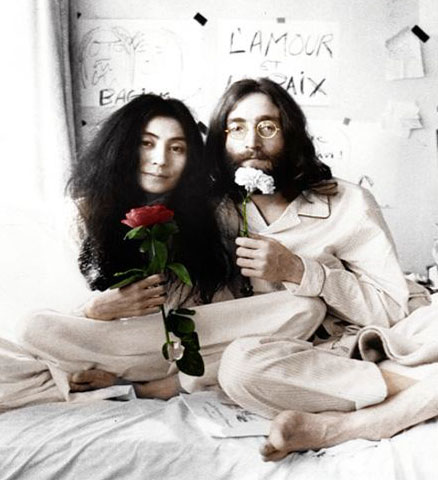

I could not forget this silly rumor. It kept growing in my mind, into a sort of science-fiction, parallel-world scenario in which Ono’s brand of time-and-space-defying artworks foreshadowed what would come to be the digitally plugged-in lifestyle we have now. As with all Fluxus artists and practitioners of post-WWII live art, Ono’s work took art out of museums into the street, breaking down socioeconomical barriers that traditionally existed between those who can afford works or art and those who don’t [ii]. She, with Lennon, took these "new art" applications a step further, using their celebrity as a medium to deliver their anti-war messages, or even turning their marriage into an act symbolizing breaking down of barriers that existed between cultures and classes. The Beatles seemed a small casualty. The "present" of The

Heart of No Place

is set in 1999, with flashbacks to 1979 when Y. meets her

husband, The Artist Known as John –– or simply, JOHN. The time frame was

shifted by a decade from

the real Ono-Lennon saga

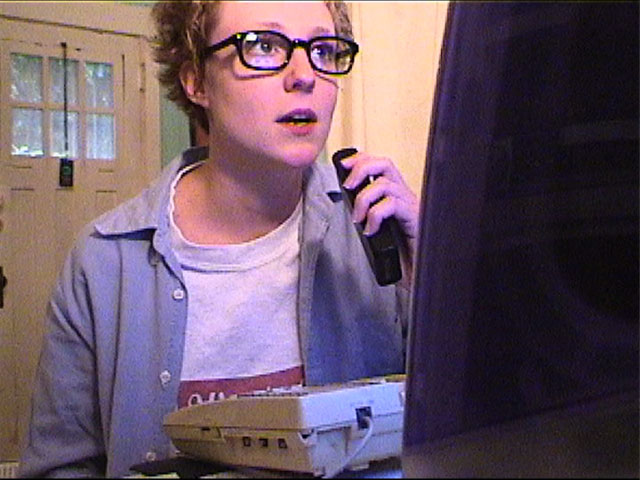

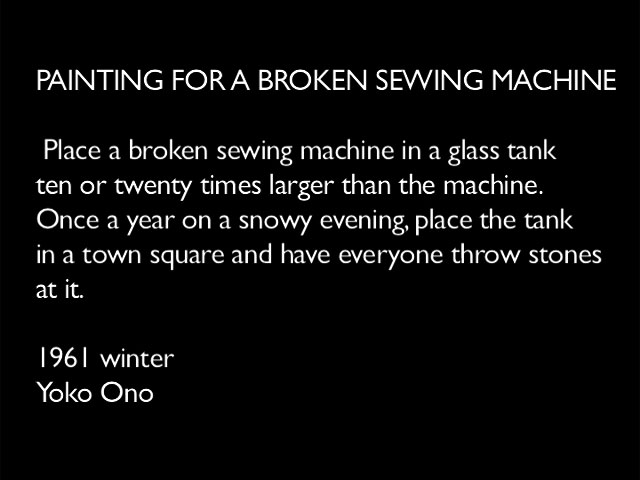

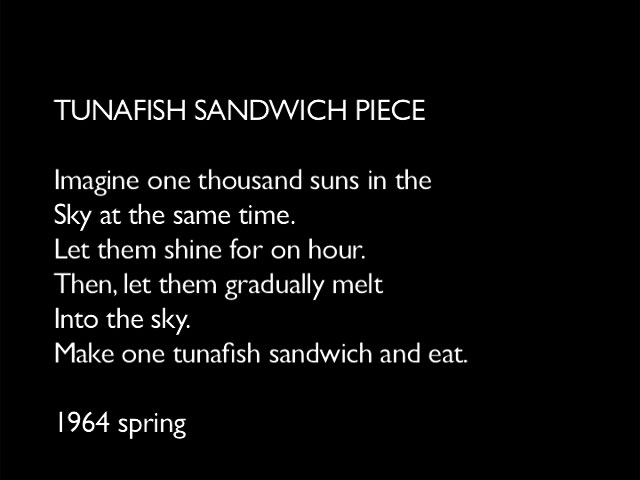

The idea of Ono’s work as precursors to our digital culture is

presented by the character Andrea, a young writer who worships Y. She calls

Y.’s "Task Haikus," a series of writings modeled after Ono’s Instruction

Paintings,

a "virtual theater": choreographed experiences compacted into a few written

lines. Instead of going to a theater or a museum, the experience can be had

at home, simply by engaging the viewer’s own imagination. (For the scene of

Y.’s 1979 gallery opening, a series of type-written index cards were framed

and installed in a gallery as representations of these "Haikus.") On the

phone with Andrea, Y. visualizes a scene The idea of the written

language as a media container of portable, virtual dramatic experiences is

expanded as Y. recalls scenes from her youth in

Tokyo Y. is at first surprised

by Andrea’s interpretation, but eventually agrees with her in tracing the

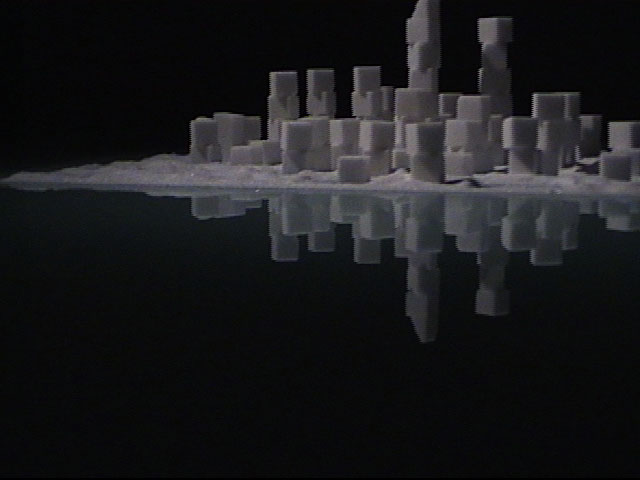

origin of her work to postwar Japan’s rapid population growth and

urbanization. She confesses that it did not make any sense to be making

large, cumbersome objects in this environment. Flashbacks show Y. meeting her

husband, the Artist Known as John ("JOHN"), at her 1979 exhibition, then,

walking in a park

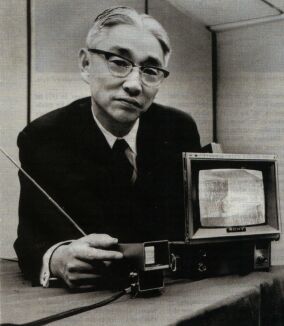

Andrea then asks Y. to comment on a symbiotic relationship between the United States and Japan in developing technology. This is, as Y. points out to the younger woman, just the opposite of what the American public felt in the late 20th century, when Japanese improvements on products closely identified with the American lifestyle, i.e., automobile and television, were blamed for unemployment and trade deficit. Seldom talked about was –– and still is –– the fact that American technology was licensed to Japanese companies during the postwar years as part of the U.S. efforts to strengthen the Japanese economy; a happy ally was a loyal ally in the U.S.’s "war" against Soviet Union. [v] [vi] [vii] Andrea says: "Japan would come up with a better hardware. They [Americans] will get a little grumpy for a while . . ." Y. replies: "Then the soft will change to suit the new hardware. Never thought of it like that." When Andrea meets Y. for

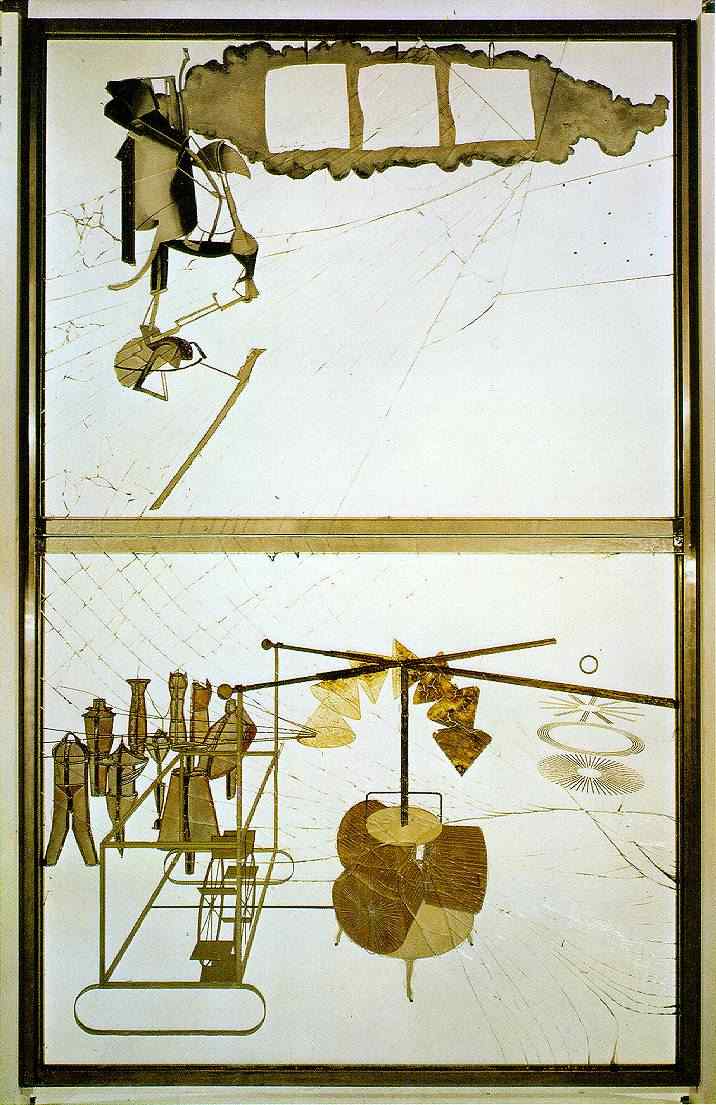

the first time at the opening of her 1999 exhibition (sculptural installation

"Two Brides," taking inspiration from both Ono’s Instruction Painting [viii]

and Duchamp’s

The

Large Glass By comparing it to Morph, Andrea is referring to what happens to the faces when they are run together as a filmstrip: When images that are similar in proportion, such as human faces, are shown in rapid succession in a motion sequence, the eyes perceive the images as blended. The viewer is free to imagine the image that emerges from this blur to be, as Y. wistfully puts it, "an essence of mankind." Andrea points out to Y: "This has been a much-imitated idea." This associative interpretation of "ON FILM NO. 4" sprang from my experience of working in 1986-87 as a photographer on L.A. Disc, a laserdisc project that aimed (I left the project before its completion) to capture scenes from Los Angeles, utilizing the then-novel digital disc’s playback capability that gave the viewer an option of watching the footages as films, or viewing each frame as one would a catalog of still images. Of course, the mainstream use of digital disc medium now is duplication of theatrical films –– with the definition of "interactivity" expanded beyond variations in playback speed. This experience of shooting a quantity of still images to work as sequences, however, led to my work with slide animation in the 1990s. Andrea concludes her first conversation with Y. on her own, slightly dystopian note: "information red dwarf theory (actually, the correct term for a star at its end stage of evolution is "white dwarf)," with which she elaborates on our culture’s tendency to recycle the old content ideas when a new platform –– like internet or vastly expanded digital storage –– opens up.

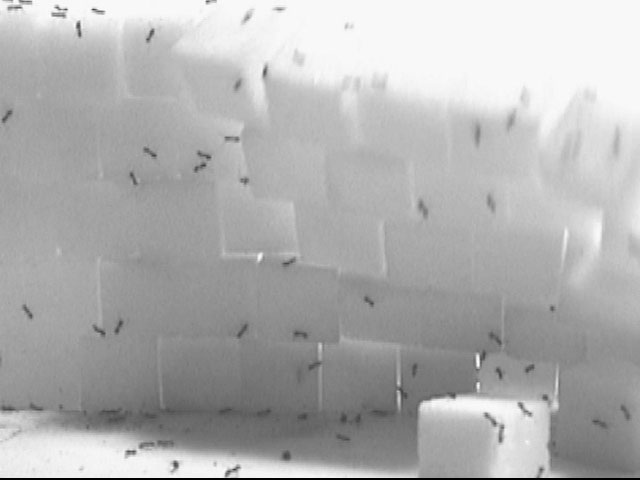

Although Y. professes to be "not a technophile," her private life is permeated with digital media. In the opening sequence we see her surfing the web and finding the database of the war dead (this conflict is simply called "The War" in the film, as the U.S. has been in a perpetual state of war), as she ruminates on the destination of such data: "from black granite to Technicolor." The scene combines live footage shot with slide animation and digital animation to create a ghostly wall of names. She later tells her Assistant –– who has also lost his partner –– that she finds herself looking for digital representations of her dead husband. She is both fascinated by the fact that there are so many incarnations of him in the consumer-created media, and disturbed by the fact each blogger "seems to claim an intimate knowledge of him." The Assistant reassures her that it’s because JOHN’s songs stirs varied, personal responses in his listeners. Y. and the Assistant

discuss the list of the war dead, memorials to the victims of AIDS and even a

virtual cemetery for dead Tamagotchis (a "virtual pet" popular in the early

‘90s). Y. marvels aloud how this internet culture has been created from a

mere figment of imagination. She believes "if enough people believed in

something, it became real" –– Ono’s

Wish Tree

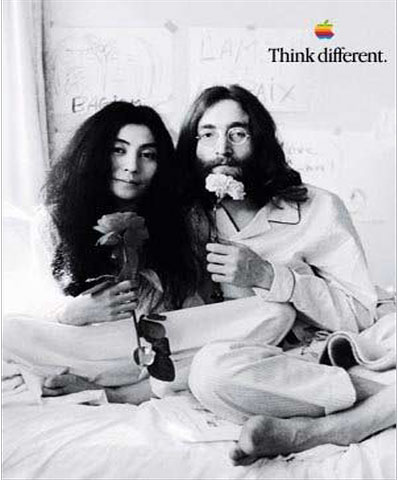

Y. is approached by Daniel Mohn, a visionary founder and CEO

of Monosoft to appear, with her late husband, in its advertisement campaign.

(Inspired by Ono & Lennon on

Apple billboards Mohn tells Y.: Y. counters that the Western bloc’s relative, material wealth had made itself seem glamorous to people living in Communist states. Mohn replies:

Mohn is talking about the sort of virtual consumption facilitated by his products –– his idea is echoed by Andrea, who counts Y. among the pioneers of mediated experiences and post-object art. [xii] But Y., having just learned that Monosoft is expanding its business to film and music, imagines Monosoft would function like movie studios and record labels of the 20th century. Like Monosoft’s intended consumers, she has no frame of reference other than the old model of the content industry. iPod went on sale in 2001, mainstreaming what had been digital piracy; Before Apple, Sony was already in business in the content industry as CBS/Sony when they introduced compact discs (1982) and Discman (1984), and would later acquire both CBS Records (1987) and Columbia Pictures (1989). [xiii] As someone with roots in the 20th-century avant-garde, she is naturally wary of Capitalism and consumer technology co-opting the creative energies of artists and misrepresenting, or even compromising, their work. Mohn for his part is on another mission, fueled by his own vision. He argues that transnational corporations are helping developing economies by creating infrastructures as a way out of "tourist economy," and that the wars in the 20th century were "spasms" out of old colonialist economy. He is a neoliberal who believes in the growing global communication network and the free-market Transnationalism it supports as harbingers of social change for the better. Y., on the other hand, suspects it will lead to exploitation of developing economies and exacerbate social inequality. To Y.’s contention that Monosoft is using the music and the likenesses of artists like JOHN to improve their image, he replies: "To enhance. And to remind everybody that software isn't just for computers." Mohn defines "the soft" as "the human factor," representative of the creative and/or intellectual process. He calls the 21st Century "the Century of the Soft" and predicts:

Y. replies: "Like Renaissance."

Mohn reminds Y. that technological innovations has enabled all to be artists:

Y., too, has been enabling her viewers by making artworks that can only be completed by them, Fluxus-style. Mohn follows up:

He has learned from Akio Morita

The artist has referred often to her work as a way to create

desire. "All my works are a form of wishing. Keep wishing while you

participate."

[xiv]

Mohn thus becomes Y.’s shadow twin, the flip side of a coin ––

their paths both lead to a new world, one through consumer technology, and

the other, through a more personal practice of art-making. In her vision, Y.

sees in a deserted museum a giant, egg-shaped globe. Inside, a naked man

curled in fetal position is writhing: Dali’s

Geopoliticus Child Witnessing

the Birth of the New Man

Art opening guests pitch in throughout the film, reevaluating Ono and Lennon’s –– Y. and JOHN’s –– work. These scenes, shot in a faux-interview style that culminates in the film’s "Guitar Envy" chapter, intentionally blur the line between the original (Ono and Lennon) and the fictional. One guest states: "They recognized their fame, or notoriety, as a medium. And their lives became the message." Two Art Critics, played by pioneering performance-art duo Bob & Bob, add: "20th century art was about the medium . . . In the second half of the century, artists . . . dispensed with the traditional medium. Their collaboration, on the other hand, went far beyond by adapting the pre-existing network of mass media and exalted the content into message." More guests comment on culture, commodity and the global culture. Some were ultimately cut from the finished film: "Access –– not ownership –– defines wealth"; "They were the first globally recognizable brand." Others survived the edit –– two Guests, in Che Guevara T-shirts (the actors/interviewees’ own costume choices) nod at each other in approval: "During that war, Capitalism came to be known as "Free Trade"

"All wars are trade wars."

Yet another explains America’s cultural domination in the postwar world: She leaves the thought unfinished; what would follow, of course, are the Beatles and the British Invasion. Later in the film, a History Professor (Dorothy Jensen Payne, 1921-2010) explains the European brain drain that vitalized the American postwar culture: "Europe was devastated. Not only by bombs but by emigration of its minds." While working on her glass piece, Y. hears in her head, another contribution to the commentary pool in Daniel Mohn’s voice: This was written in tribute to my father Shoji Obara (1926-1998) who studied the development of transportation networks in Japan.

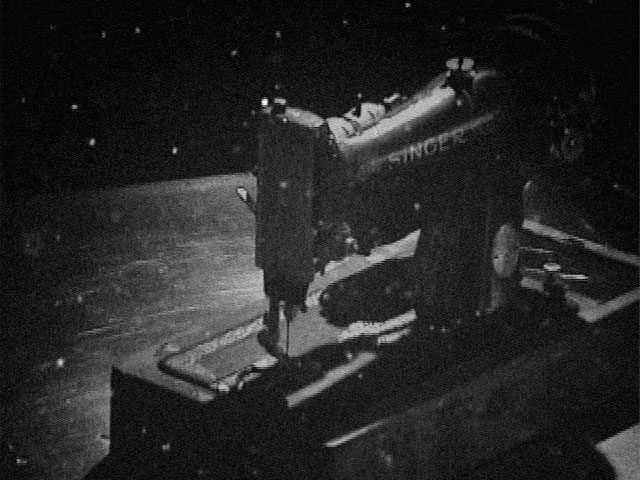

Several events comprise the "catalyst" leading to the film’s

emotional resolution (as a fictional artwork, the film does not propose a

social or political solution). In

one

The

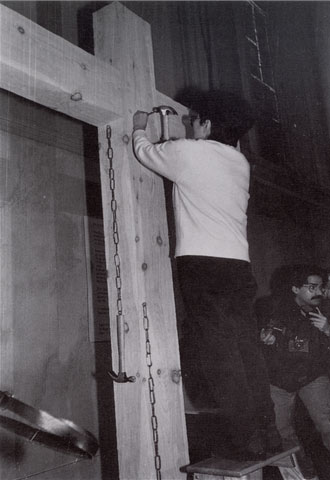

first half of final chapter shows Y.’s inner experience of performing her

"Nailing Piece," inspired by Ono’s

Painting to Hammer a Nail In There are no religious wars/There are no ideological wars/ All wars are trade wars. Does the sun travel westward?/Does the wind?" Phrase "virtual money" was much on my mind during the making of this movie. Of course, it came down as the credit crisis as I was finishing it (2008-2009).

When the film won the "Best Film" award at London Independent Film Festival, the online catalogue described it "a modern-art reinterpretation of Yoko Ono’s life and work." The writer was right, but only partially. It is a postmodern, rather than modern, reinterpretation of Ono’s work, and an attempt at repositioning them as an inspiration shared by the new generation of art- and mediamakers. It is also a search for social and historical background for why Ono’s work Needless to say, Ono herself charges ahead, completely plugged-in. In addition to continuation of her "traditional" outputs in installations and sculptures that disseminate her messages for world peace, she generously allows her music to be re-mixed by younger musicians, allowing herself to be replicated through sampling. |

Additional Readings:

List of Ono works referenced in the film The Heart of No Place Production Notes |

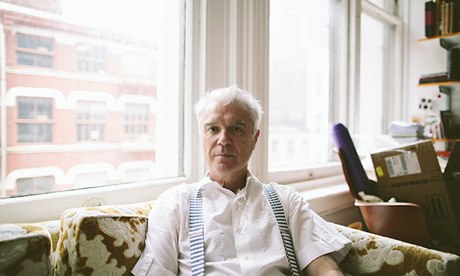

David Byrne: "The internet will suck all creative content out of the world," The Guardian, 11 October, 2013

David Byrne: "The internet will suck all creative content out of the world," The Guardian, 11 October, 2013