The sun

is a goddess in Japan. When I learned of the Baltic sun goddess Saulé, I

searched for other female sun deities: the Celtic Sul, the Germanic Sól,

Wurusemu

Wurusemu (1550-1200 BCE), The Metropolitan Museum of Art

of the Hittites and the Egyptian

Hathor

Hathor, Museo Egizio, Torino

among them. But I couldn't

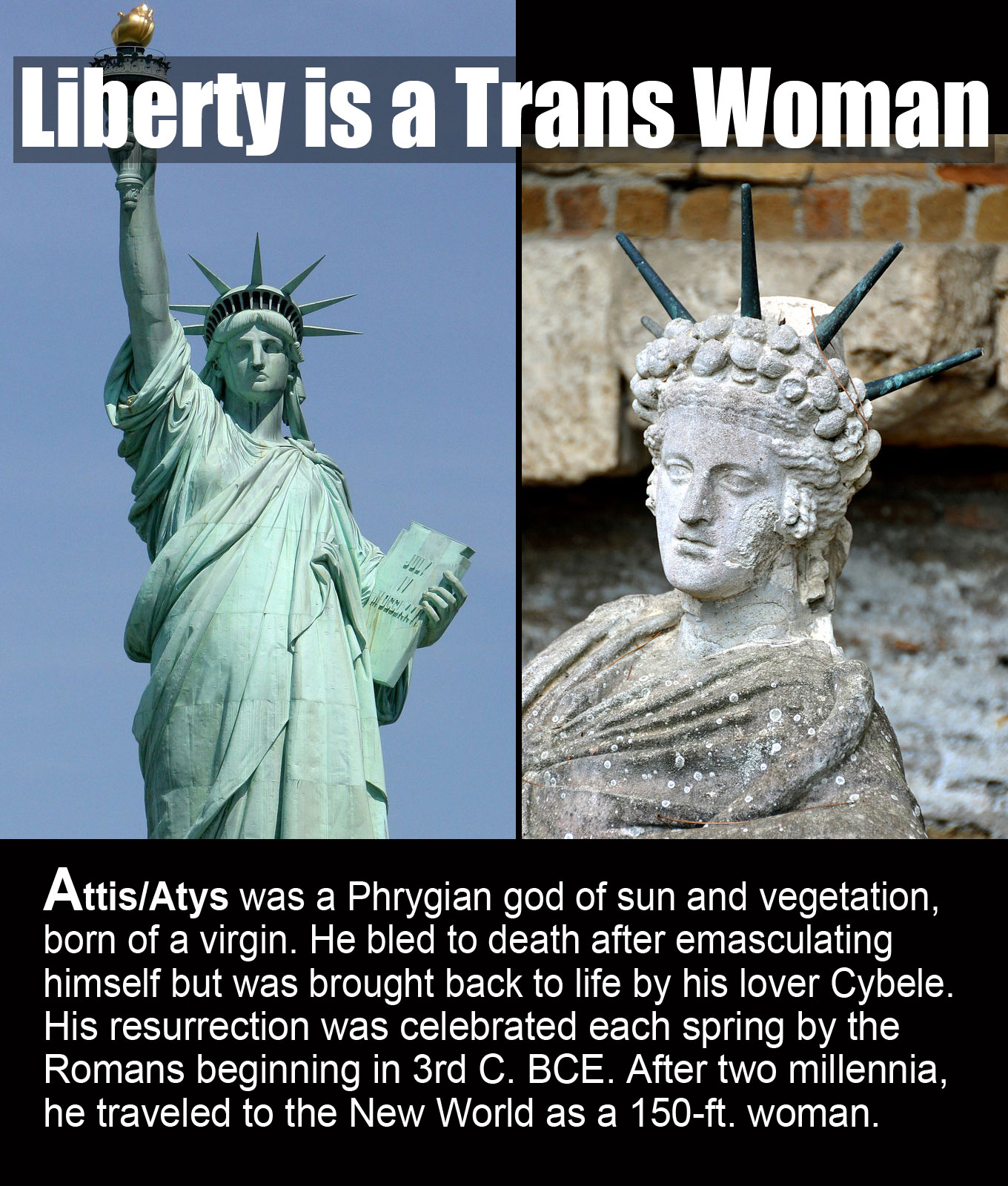

find the figure behind the Statue of Liberty, who, with her sun diadem, is

obviously connected to the sun. She has been variously identified as Columbia

personifying the United States, modeled after the sculptor Frédéric Bartholdi's

mother or an emancipated African slave, or –– of course –– the Roman goddess

Libertas

Arnold Böcklin, Die Freiheit (1891).

But none of these explain the rays of sun on her head.

There is the

Colossus of Rhodes

Salvador Dalí, The Colossus of Rhodes (1954)

, one of the Seven

Wonders of the Ancient World, said to have represented Helios. But Helios is

one among other male sun deities such as Apollo and Mithra. The intended effect of

the two giant statues may be the same, but how to explain the sex change?

The

breakthrough came when I returned to Sir James George Frazer's The Golden

Bough for

information on pre-Christian customs that influenced the modern celebration of

Easter:

|

“Another

one of those gods whose supposed death and resurrection struck such deep roots

into the faith and ritual of Western Asia is Attis. He was to Phrygia what

Adonis was to Syria. Like Adonis, he appears to have been a god of vegetation,

and his death and resurrection were annually mourned and rejoiced over at a

festival in spring. Attis was said to have been a fair young shepherd or

herdsman beloved by

Cybele

Cybele on a cart drawn by lions (2 century CE), Roman, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

, the Mother of the Gods, a great Asiatic goddess of

fertility, who had her chief home in Phrygia. Some held that Attis was her son.

His birth, like that of many other heroes, is said to have been miraculous. His

mother, Nana, was a virgin, who conceived by putting a ripe almond or a

pomegranate in her bosom.

“Two different

accounts of the death of Attis were current. According to the one he was killed

by a boar, like Adonis. According to the other he unmanned himself under a

pine-tree, and bled to death on the spot. The latter is said to have been the

local story told by the people of Pessinus, a great seat of the worship of

Cybele, and the whole legend of which the story forms a part is stamped with a

character of rudeness and savagery that speaks strongly for its antiquity."

|

|

Google

image search yielded the above, a statue of Attis wearing a sun diadem, at the

shrine of Magna Mater (the Great Mother = Cybele), Ostia, near Rome

(the original statue

Attis at the Vatican Museum

is in the Vatican Museum). The reclining deity holds a pomegranate in his hand.

The symbolism is clear: Attis’s resurrection represents the return of the season of

fertility; it was eating of this fruit that condemned Persepone to her

amphibious existence –– spending half a year underground and the other half

above, mirroring the cycle of growth and the decline of vegetation.

Worship

of Cybele was brought to Rome during the Second Punic War (218 – 201BCE), and

her annual festival, including the celebration of the resurrection of her consort

Attis, was celebrated at roughly the same time as the later Christian celebration

of Easter.

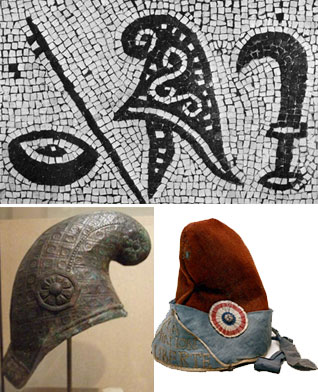

Although the Magna Mater Attis wears a sun diadem as

a sun deity, he is more often

represented

Attis as Youth (2nd c. CE), Cabinet des Médailles, Paris wearing a

Phrygian cap

Phrygian caps

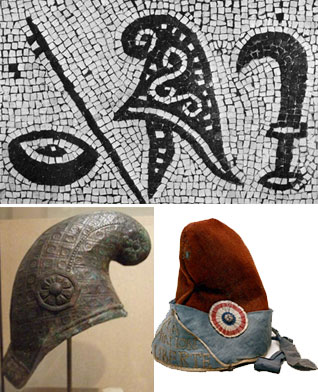

–– which

happens to be the headgear of choice of the goddess Libertas. It is easy to imagine

that the sculptor Bartholdi had originally put a Phrygian cap on his Liberty. But

the figure of

Liberté

Eugène Delacroix, Liberty Leading the People (1830) and her Phrygian cap had become solidly associated with

the nation of France via the figure of Marianne. Her presence at the port of

entry would have been, at best, confusing to European immigrants. So, in order

to avoid offending the American national sensibility, Bartholdi looked for an

alternative headgear for this gift to the United States.

Bartholdi must have been familiar with the statue of

the reclining Attis –– here wearing a sun diadem. Bartholdi could have even

been led, via Attis, to let his Liberty assume a similar pose –– wearing a

sun diadem, holding a torch above her head –– as Colossus. It was not much of

an artistic license Bartholdi took.