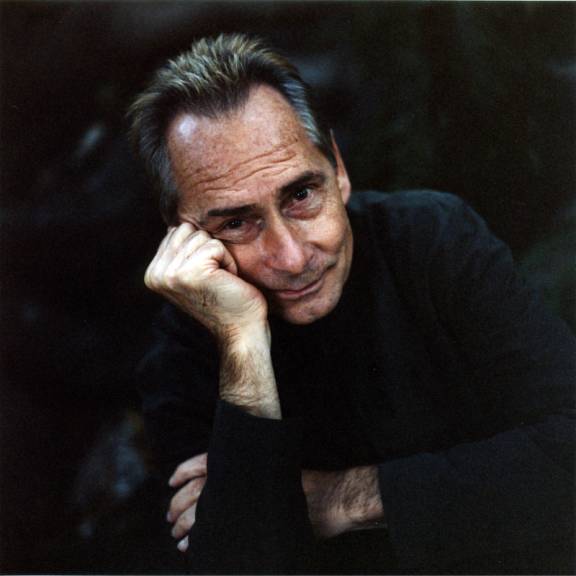

Taboo

Jon Hassell, hyperreality

and the magic of tone

Since 1977, the

Los Angeles-based composer-trumpeter Jon Hassell has recorded 11 solo

albums that blur the boundaries separating “serious” and popular music.

He’s collaborated with an eclectic group of artists, including

Brian Eno;

Farafina, a traditional ensemble of drummers and dancers from Burkina Faso;

director Peter Sellars; fashion designers Issey Miyake and Rei Kawakubo;

choreographers Merce Cunningham and Alvin Ailey; and the Kronos Quartet.

Hassell is also the inventor of Fourth World, a hugely

influential composed and improvised music that hybridizes African-derived

polyrhythms, Indian microtonality and Balinese sonorities, melted through

recombinant aesthetics made possible by digital technology. Quite often,

Fourth World is none of the above. And lately, Hassell has explored the

wonders of playing music absolutely straight.

Fourth World is not just a musical style but a way of

viewing life itself, rooted in its creator’s past, in Memphis, Tennessee.

“My father had a cornet lying around the house, so I played that, used to

lock myself in the bathroom, play ‘Stormy Weather’ and stuff like that. I

heard Stan Kenton on the radio, I heard Les Baxter,

Duke Ellington and Juan

Tizol’s ‘Caravan,’ and Ravel –– a permanent Technicolor oasis in my spirit.”

Hassell left the South for the Eastman School, where

he studied composition and allied himself with the 12-tone types into

Webern and Schoenberg and Berg, et al. After a stint in the Army, he earned

a master’s in composition and nearly completed his Ph.D. in musicology at

Catholic University of America. But by then he’d discovered Berio and

Stockhausen, and “I just had to find out where these blocks of notes were

going.” He went to Cologne to study with Stockhausen, from whom Hassell

learned a lot about the wherefores and could-be’s of electronic music. “I

saw how one applied statistical means; there were exercises where you’d

notate short-wave radio bits, you’d see how scores were constructed.

Stockhausen started a different point of view: Instead of building sounds

up by defining all the parameters, start with the whole and then infer the

parts of that whole.”

Returning

to America, Hassell met Terry Riley, who was at that time recording his classic In

C. This was

Hassell’s first contact with American Minimalism, whose mesmerizing

repeated figures brought him home to something he’d missed: sensuality. “I

remember Terry calling all of that other music over there, the post-Webern

things, ‘neurotic.’ And it was so self-evident –– this is the sound of

Freud in Vienna, and Schiele and all that.” Hassell’s a subsequent work

with La Monte Young found him further exploring minimalistic music that

reconciled the body, mind and spirit, a “vertical” way of playing and

listening to mutating structures created by overtones in flux.

There

is an instantly identifiable “Hassell sound.” On his best-known albums,

including Possible Musics (1980) and Dream Theory in Malaya (1981), it’s not at all like

“trumpet”; amid the pitter-pattering rhythms and generally steamy ambiance,

you think you’re hearing voices, huddled together, cooing, giggling,

chanting. In fact, you’re hearing Hassell’s voice, or, rather, his mouth

and voice box –– he’s singing with his trumpet. It’s a technique he

developed in his studies with Indian vocal master Pandit Pran Nath, whom he

met in the ’70s through both Young and Riley, who had studied with Pran

Nath in India. At around the same time, Hassell got into Miles Davis –– On

the Corner,

that era –– and started playing with a wah-wah pedal. “That’s when the

daylight world and the night world came together; the daylight world is,

you’re painting white-on-white painting, as in the Minimalist-school

compositional effect, and then at night, when it comes to groove, you’re

putting on Miles.”

Whence comes the Fourth World. “I saw how Indian

music had structure and sensuality at the same time, so rather than

literally using the tamboura, I translated the tamboura into an electronic

cluster of samples or an electronic drone, and then added whatever rhythmic

elements one can infer. I didn’t want to reference; I wanted to get a new

idea about what could be.” With Pran Nath, Hassell learned that there’s no

limit to musical variation when one coils among the notes. “There are 12

notes between B and C, and there’s all that other space in between, and

you’re doing a little tie, right? I heard Pran Nath start off, and 15

minutes into it I realized he’d gone only two or three half-steps, because

of all the possible ways of making the curves.

“In

the Indian tradition they say that all instruments come from the voice, and

my technique came from having to learn that shape-making from the voice.

Timbre and musical expression are interrelated –– a lot of Indian instruments

and voices derive from that, because you can’t drive a truck [tuba] in a

graceful curve; it has to be something which is malleable enough to make

all these curves [sitar, voice]. I find the tiniest vibration that I can

with the mouthpiece and then try and trick myself into thinking I’m still

playing only the mouthpiece. If I can do that, I can do anything.”

Hassell’s

electronic devices have often inspired the pieces themselves. “I was

learning to do the vocal-like slide technique, then this harmonizer [a

digital multiplying effect] came along and I started playing in parallel

fourths or fifths, sort of mirroring the birth of polyphony, how plainsong

began with just one line and then, given various ranges of voices, started

singing in parallels, and then somebody got the idea to play on top of

that, etc.” His use of harmonizer can approach the orchestral –– “Blue

Night” on Dressing for Pleasure, for example, on which, via a switching device, one

harmonizer plays into another and into another.

Hassell

took sampling into the realms of hyperreality on the 1983 Aka-Dabari-Java

–– Magic Realism,

where his supercollaging found him using one second of a gamelan, one

second of a voice, one second of Yma Sumac/Les Baxter orchestration, with a

drummer playing underneath it all. He addressed “the poetic possibilities

of digital transformations…a background mosaic of frozen moments…a sonic

texture like a Mona Lisa which, in close-up, reveals itself to be made up of tiny

reproductions of the Taj Mahal.” Here Fourth World became what Hassell

called a “coffee-colored classical music of the future.”

Then

Hassell heard Hank Shocklee’s stupefyingly complex collages on Public

Enemy’s It Takes a Nation of Millions To Hold Us Back and saw that collage ––

techniques and philosophies directly deriving from Stockhausen and the

musique concrŹte crowd of the ’50s –– had entered the popular

consciousness. “It was very related to Pygmy music –– it was based on what

was around them that they picked up in the morning, what the Pygmies heard,

Pygmies imitating birdcalls and rhythms coming out of spear blades and

things like that. And here you’ve got kids living in the Bronx and whose

environment is the radio. Hip-hop is like the music of the loudspeaker,

it’s doing the same thing Pygmies did with birdcalls.”

The

advent of MIDI and sophisticated sampling technology led Hassell into new

realms with the albums City: Works of Fiction and Dressing for Pleasure (whose title derives from

the fetish world), complexly faceted and funky works on which he

extrapolated from hip-hop into how far sampling could be taken. Not

coincidentally, Shocklee had cited Brian Eno and David Byrne’s My Life

in the Bush of Ghosts as an influence, a record whose gambit of planting ethnic

samples atop electric rhythms Eno and Byrne had, after consulting with

Hassell, taken for themselves. “I should do a record where I sample My

Life in the Bush of Ghosts,” he says. These days Eno and Hassell are good friends,

though he doesn’t see much of Byrne.

Considering

the devilishly electronic nature of Hassell’s previous albums, I had to

wonder about his current entirely different course, soundwise. His new

album, Fascinoma, was recorded in a church in Santa Barbara, on magnetic

tape, with one stereo microphone and no digital effects. Perhaps Hassell

has experienced a bit of electronic-media overload these last few years ––

or suffered too much of its ensuing clever irony.

There’s

also the problem of the Hassell-derived “future-primitive” musical kitsch

(ethnic samples + electronics) we suffer in every elevator. “Inevitably,

you question, Well, gee, would it have been better for this never to have

happened? You come to a certain point in collective thought where

progressives suddenly become the carriers of orthodoxy. Of course, the ad

world is all ready to pick up the latest contrarian view and turn it into a

commercial –– William Burroughs doing Nike ads, like that.”

Fascinoma was produced by the

ubiquitous yet unobtrusive

Ry Cooder, whom Hassell calls a “spirit

catcher,” a master of “authentica.” The album sees Hassell –– aided by a

team that includes pianist Jacky Terrasson, bansuri (flute) player Ronu

Majumdar, guitarist-clarinetist Rick Cox and percussionist Jamie Muhoberac

–– going back to the fragrant songs he loved as a youth (such as “Nature

Boy,” “Poinciana” and “Caravan”), “touchstones, like little windows opening

out of my 1950s world.”

The album digs deep into the mysteries of pure tone

–– almost. While it boasts an authentic audiophiliac analog experience,

that’s not quite an authentic way of describing it, as the players also

employed samples, and the performances were edited. But the technology is

minimal, and most of the cuts were played straight through, with little

rehearsal. The church setting allowed Hassell to build on the idea of not

creating something from scratch, but having to harmonize with the beauty

that’s contained in a room.

“There

clearly is a relationship between timbre and what kind of music you play;

they’re organically related. So, when a certain quota of beauty is already

fulfilled when you walk into the room, ‘Nature Boy’ feels as right to do as

the B-minor Mass.”

Fascinoma’s way of recording has given

Hassell ideas for future projects. “I’d love to do a record with Jimmy

Scott, in that intimate one-microphone way. And I’d like to do a record

with Jočo Gilberto, just me and him up in the church. I’ve been so

enchanted by his sensuality and his rhythmic grace and everything, you

could put it up with the masterworks of the world.” Gilberto’s music, says

Hassell, is unassailable.

“There

is beauty, like naked beauty. If you want to talk yourself out of it, okay,

go ahead and talk yourself out of it.”

Digital

technology has given birth to musical methods by which one can easily mix

’n’ match elements from as many “cultures” as one pleases, a situation that

has led to cries of “colonialism” toward artists who weren’t deemed to be

“respecting the source material.” It’s always phrased this way –– and one

wonders how such respect could ever be sufficiently demonstrated. One is

reminded of the Brazilian Tropicalistas of the late ’60s, early ’70s,

proudly proclaiming their “cannibalization” of all and any music (European

included) they could get their hands on, or the Indian musicians who

adapted the violin for their ragas.

Who

may cannibalize without guilt? Jon Hassell? Maybe so –– one has only to

listen to see that he has consistently created something new out of his

lovingly borrowed elements.

“The

crux of it is, Is this better than the thing you’ve appropriated? Does this

add anything to the world, or would it be better to hear the source that

you took from?” Remember that Hassell’s early inspiration came from career

inauthenticists such as exotica king Les Baxter, whose purpose in life was

to provide people with pleasurable escape. It’s a stretch, but you could

say that Les Baxter’s fake music was honest in its guileless hunger for

adventure.

“It’s so simple and yet it’s so difficult. I keep

saying, ‘Put yourself in a dark room and keep asking the question, What is

it that I really like?’ There are things you’ve been told that you like,

things you’ve been commissioned to like, and things you’ve been told it’s

not right to like. I don’t see the difference in kids playing out now; I

pray that they hit the spot where they start thinking, ‘What is it that I

really like? And not what has been foisted on me.’”

Hassell,

like a lot of musicians in L.A., has had his stab at composing for big

Hollywood films, including the soundtrack for Wim Wenders’ The End of Violence. He recently scored Wenders’

upcoming The Million Dollar Hotel, in which he also appears onscreen as a

down-and-out musician living in a Skid Row dive. For his acting debut,

Hassell drew on his musical side, and he enjoyed it.

“In

attempting to present yourself, you have to groom yourself to perform

onstage; it’s the same dynamic –– you want to be yourself as much as

possible, be as comfortable as possible. It’s a lot easier being myself

without an instrument on my mouth. So it was fun, a lotta fun.” He laughs.

“I play a shabby trumpet player.”

|

|