|

Forever Changes Forever Changes

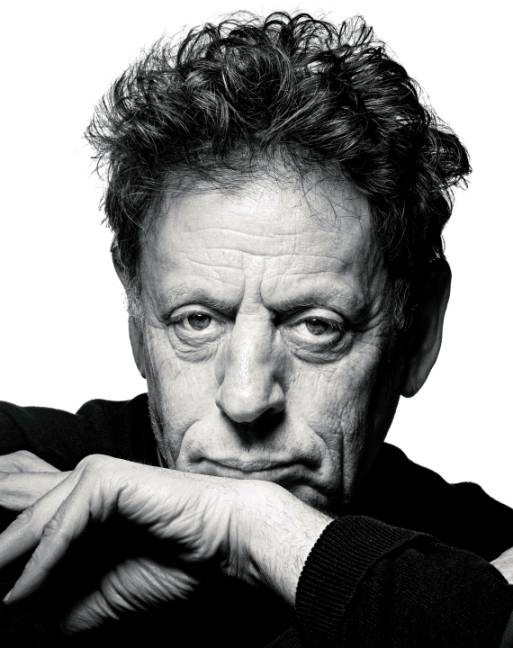

Philip

Glass

in the time of music

One

of the largest-looming and most controversial composers of the last

century, Philip Glass pioneered the use of repetitive, hypnotic structures ––

commonly referred to as Minimalism –– in a now vast body of work that got

underway in the late ‘60s with explorations of purely formal concerns in

pieces such as Music in Fifths, Music in Similar Motion and Music With Changing

Parts, works

that were performed with his chugging locomotive of an electric ensemble.

The former NYC cab driver from Baltimore, who’d studied music with William

Bergsma, Vincent Pershichetti, Darius Milhaud and Nadia Boulanger,

eventually collaborated with Ravi Shankar, which profoundly altered his

views on composition, and which in part led to his series of larger scale

operas and symphonies for orchestra, including the masterpiece Einstein

on the Beach

(1977), Satyagraha (1985) and Akhnaten (1986). In more recent times audiences have become familiar

with Glass’ scores for a number of high-profile films and documentaries,

such as The Truman Show, The Hours, Kundun and Cassandra’s Dream.

The Philip Glass

Ensemble and the Los Angeles Philharmonic performed several of Glass’

varied works at the Hollywood Bowl on July 23. The program featured Glass’

well-known score for Godfrey Reggio’s Koyaanisqatsi: Life Out of Balance (1982), a wordlessy

unfolding explosion of images detailing our dying relationship with Mother

Earth. The film was screened in synchronization with the performance of the

music.

Over the phone from Linz, Austria, where he was performing Kepler, a new opera based on the

life of the astronomer, Glass discussed the modern composer’s new roles in

mating sound and image for theater and film.

BLUEFAT: By the time Koyaanisqatsi came about,

you were already well established in areas combining music and visuals.

PHILIP

GLASS: At

that point I was 41 years old, and I had been playing with my ensemble for

10 years. Einstein on the Beach was four years old, and the opera Satyagraha was composed by then. So I

didn’t really consider myself a film composer, and at that time I wasn’t.

Godfrey Reggio approached me with the idea of working with this film, and I

said, “Well, I don’t write film music.” What a way to start in the film

business, huh? But when I saw what he was doing, I was so impressed, and I

said, okay, I can do this.

Godfrey wanted to work in a collaborative form, and we established a

rapport in a way of working which I’ve since been able to do occasionally,

as with Errol Morris and other independent filmmakers doing unusual kinds

of documentary films, such as Morris’ A Brief History of Time. I’ve been able to work with

other people in which the music enters the creative process at a very early

stage; I’ve done that with Martin Scorcese’s Kundun. And I just finished this

film with Bernard Rose called Mr. Nice, which was done completely that way; I was

writing from the film script and scenario, and then wrote the pieces for

where they’re going to fit in the film; then the film is edited with the

music not in final form but in a recognizable form.

That’s far from ideal; it’s very hard to do. I’ve done a lot of

other films in the way Hollywood films are usually done, which is, it

becomes part of the post-production process. There were some very good

films done that way; The Hours was done that way; even with Woody Allen [Cassandra’s

Dream], he

had already completed filming, but I was able to make contributions very

independently with him.

(continued)

|

|